Important pan-European news stories, such as the Ukraine crisis, are often overlooked by Europe’s media – including the quality press – according to new research. A comparative analysis of the conflict in Ukraine, conducted across 13 countries, reveals new information about barriers to the development of a European public sphere.

Significant variations between European countries in the amount of media coverage of Ukraine’s crisis were noted by researchers. They also found the media generally focused on the role played by President Putin in the conflict, rather than on international political issues surrounding the events in Ukraine.

Researchers from the European Journalism Observatory (EJO) analysed newspaper coverage of the Ukrainian conflict in Albania, Czech Republic, Germany, Latvia, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Switzerland, Ukraine and the United Kingdom for the study: The Ukraine Conflict and the European Media. A Comparative Study of Quality Papers in 13 European Countries.

Content analysis of two national opinion-forming newspapers in each country was conducted by university-based researchers. Analysis focused on four key political events in 2014: Euromaidan (February 18th); the Crimea referendum (March 16); the Eastern Ukraine referendum (May 11) and presidential elections (May 25). All news items and opinion pieces were analysed in the three days leading to the event and the three days after.

Attention versus neglect: How European media treated a crucial European conflict

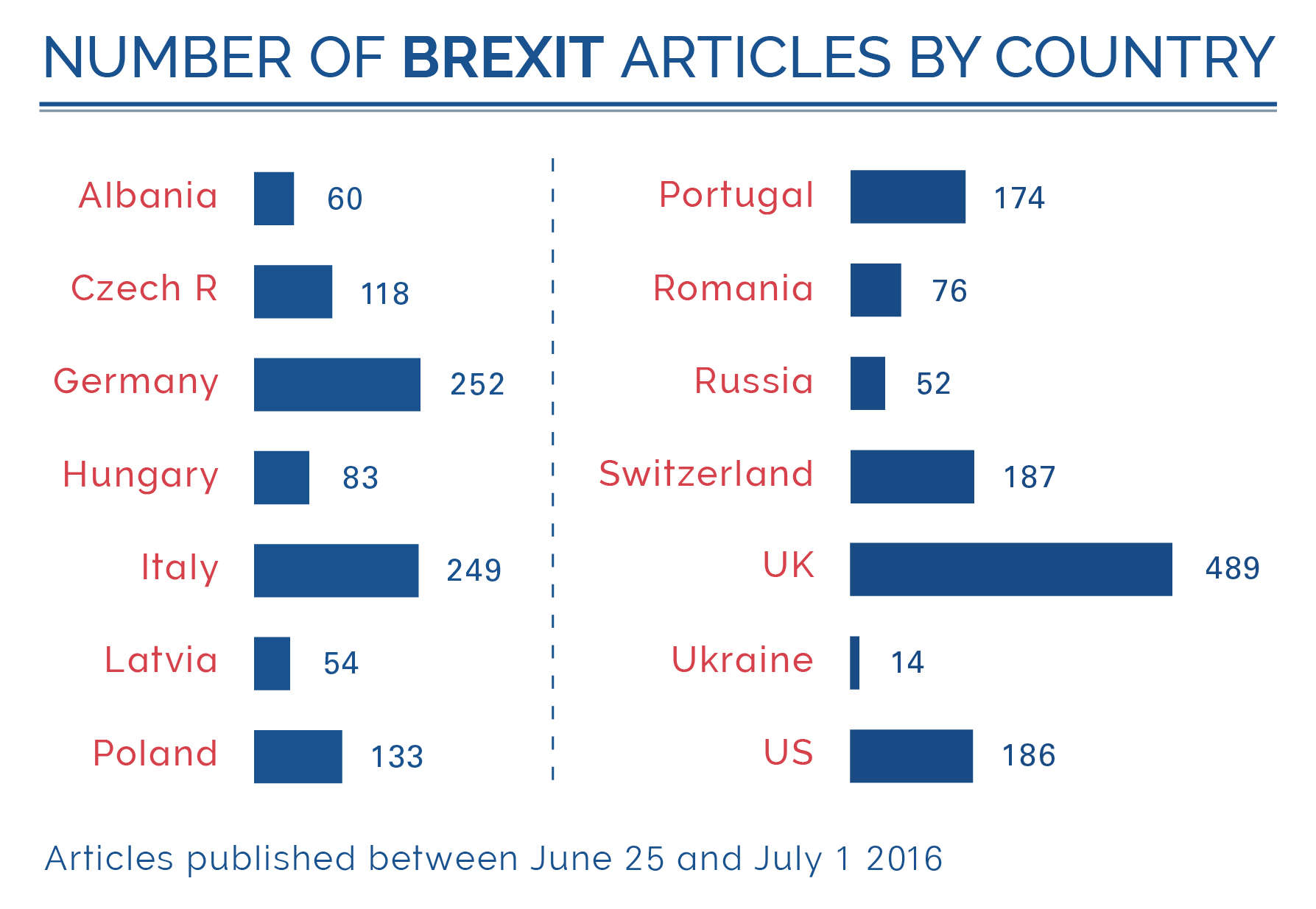

The study revealed significant variations in the amount of coverage given to the crisis. For example, while Polish and German newspapers each published more than 250 articles during the period studied, only 29 articles about the crisis appeared in Romanian newspapers in the same period.

In the Netherlands only 129 articles were published on Ukraine during the period studied. However, as Simon S. Knopper from Fontys University, points out, the Dutch media became significantly more engaged in the story later in the year, after the shooting down of Flight MH17 over Ukraine, on July 17 2014. Many Dutch nationals were among the 238 passengers and 15 crew killed.

In the United Kingdom only 129 articles on the Ukraine conflict were published in the two analysed newspapers (The Guardian and The Times) over the four dates studied. Portuguese newspapers published many more articles – a total of 164 news items over the same period.

The results for the UK seem to reflect how UK national media follow European politics. The current government’s focus on domestic issues is reflected in the country’s media coverage. Even the quality newspapers studied paid relatively little attention to the conflict in Ukraine, and thus failed to fulfil the ‘burglar alarm’ function American political scientist John Zaller ascribes to the media.

In Switzerland 237 articles were published about Ukraine during the four news events studied, with the business-oriented Neue Zürcher Zeitung providing much of the coverage.

In Central Eastern European countries, such as Latvia and the Czech Republic, with their painful memories of Soviet military intervention, relatively few articles about the conflict were published (187 in Latvia and 174 in Czech Republic).

The most extensive coverage of the conflict in Eastern Ukraine was of course provided by Ukrainian media, with 923 articles. While most international media focused on politics, Ukrainian outlets also reported on domestic events, as well as the economic consequences of the conflict for the country.

Ordinary citizens featured most prominently in Ukrainian coverage (7.6%), Ukrainian scientists and intellectuals who provided expert commentaries on the events (7.3 %), armed forces loyal to Ukraine’s provisional/new government (4.7%), victims (2.5%) and armed forces loyal to the country’s previous regime (2.4%).

Europe: Obsessed with Putin

European media generally treated EU actors as less relevant, compared to key political figures from Ukraine and Russia. The individual most featured in the coverage across Europe is Vladimir Putin (9.1% of all references). Actors from EU countries, the EU and other international organisations, as well as the US, together make up less than one fourth of the political figures mentioned.

Even though press freedom is firmly established in the EU treaty, our research appears to confirm the criticism the EU High-Level Group on Media Freedom and Pluralism in Europe directed to Central Eastern (and Southern European) media in 2013. The Group’s report concluded that press freedom and pluralism had been compromised in some countries in the region due to political influence and commercial pressure.

According to Liga Ozolina from Turiba University in Riga and Roman Hajek from the Charles University in Prague, EJO editors who analysed Ukraine coverage in Latvia and Czech Republic over the period studied, both Latvia’s Avīze, and the Czech paper, Právo, appear to have been considerably influenced by their respective national governments’ political position on Ukraine.

The study also points to the danger the current shift in media economy poses for the quality of public debate in Europe. This is more visible in Central Eastern European newsrooms which operate in increasingly unstable financial conditions, compared to Western European newsrooms.

The initial lack of attention to the conflict in the Romanian, but also in Serbian and Albanian newspapers, was likely to have been partly due to the lack of resources, even in top national papers, to maintain comprehensive foreign coverage. After the Romanian newspaper, Adevarul, sent a ‘parachute correspondent’ to Kyiv, coverage increased exponentially, and dominated the paper’s foreign agenda afterwards, Raluca Radu, of EJO Romania and Bucharest University, explains.

Coverage in Russia: Euromaidan and the Sochi Olympics

In Russia, Ukraine only started to receive media attention after Viktor Yanukovich was removed from power at the end of February 2014. For example, the Euromaidan events that preceded Yanukovich’s departure were barely covered in Russia. While an average of 20% of articles were published in other countries about the Euromaidan protests, only 3% were published in Russian newspapers studied, (state-owned Rossiyskaya Gazeta and in the country’s business-oriented and liberal Komersant).

However, the Crimea referendum, held one month after Yanukovich left Ukraine, received more attention in Russian newspapers compared to the 13-country average.

Across the period studied a total of 413 articles about Ukraine were published in the Russian media. Only 14 articles were found across the two titles during the first event, Euromaidan (3.3%); 232 articles were published about the Crimea referendum (56.2%); 107 about the Eastern Ukraine referendum (25.9%); and 60 (14.5%) about the presidential elections.

According to Anna Litvinenko, a researcher at Freie University, Berlin, formerly based at St Petersburg State University, the Russian media probably downplayed Euromaidan because the events clashed with the Sochi Olympic Games. Russian reporters were occupied within Russia and few were in Kyiv and may explain why coverage was limited.

Notably, there were few differences in coverage of the Ukraine crisis between Russia’s pro-governmental Rossiyskaya Gazeta and the country’s liberal newspaper, Kommersant. Both carried similar amounts of coverage and positioned the story in similar ways. Litvinenko said unified agenda setting factors work within Russia’s media landscape, affecting both pro-government and opposition media: the framing of the events may be different, but the amount and focus of coverage are more or less similar, she added.

Newspapers included in the study were: Albania: Panorama and Shqip; Czech Republic: Mlada Fronta Dnes and Pravo; Germany: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung and Suddeutsche Zeitung; Latvia: Diena and Latvijas Avize; Netherlands: De Telegraaf and De Volkskrant; Poland: Gazeta Wyborcza and Rzeczpospolita; Portugal: Diário de Notícias and Público; Romania: Adevarul and Romania Liberă; Russia: Kommersant and Rossiyskaya Gazeta; Serbia: Danas and Kurir; Switzerland: Neue Zürcher Zeitung and Tagesanzeiger; Ukraine: Den and Segodnya; UK: The Guardian and The Times.

Researchers were Prof. Dr. Susanne Fengler, Marcus Kreutler, Tina Bettels-Schwabbauer, Janis Brinkmann and Henrik Veldhoen, German EJO; Matilda Alku, Albanian EJO; Liga Ozolina, Latvian EJO; Dr. Michal Kus and Anna Paluch, Polish EJO; Roman Hájek and Sandra Stefanikova, Czech EJO; Dr. Dariya Orlova and Maria Teteriuk, Ukrainian EJO; Débora Medeiros, Free University Berlin, Germany; Simon S. Knopper, Fontys University, Netherlands; Stefan Georgescu, Andrei Saguna University, Romania; Anna Litvinenko, St. Petersburg State University, Russia / Free University Berlin, Germany; Filip Dingerkus and Mirco Saner, ZHAW, Switzerland; Bojana Barlovac, University of Belgrade, Serbia.

The post Research: Europe’s Media Ignore Pan-European News Stories appeared first on European Journalism Observatory - EJO.

If it fails, cruder responses may be the only ones left. But let’s hope not.

If it fails, cruder responses may be the only ones left. But let’s hope not.

Portugal

Portugal